The Lubuto Library functions as any other library. The door is open, and kids come in and out at their leisure, often between classes at school. I thought I'd share a few of my interactions with the patrons. It was quite crowded today, and I usually end up spending a lot of time with one or a small group at a time because questions arise and new books need to be drawn into the mix.

A couple of boys were looking at a book from the Mammals section, and one pointed to a white snow fox in an Arctic setting and asked if I saw these in America. It's not hard to understand why snow is often very exciting to kids in Zambia. After a short conversation about climates and foxes, he pointed to a photo of the Matterhorn and asked if I'd been there. They thought it was Mt. Everest, which was a pretty good guess. I started telling them about Switzerland and my experiences there. They immediately wanted to know more about the Alps and Switzerland. I turned to the National Geographic atlas with lots of photos and cultural information. I'm glad I traveled in Europe and studied abroad in Rome because they wanted to hear any stories I had about Europe, which I shared and backed up with library resources. They were fascinated by the canals of Amsterdam and Venice, learned the story of the Berlin Wall, etc.

A small child with very limited English swooped in to take a look at the same atlas when the other boys left. It was frustrating at first because I was having trouble explaining anything to him, and he didn't seem to be learning anything. Suddenly, he pointed to the little UK flag inside the Figi flag and declared, "England!". From there, he turned to China. I identified China on a world map. He pointed to a picture of some people on the street, and I told him they were Chinese people. Much later, he turned to the "People" section, and identified a different and randomly placed picture of Chinese people as "China". Even with his limited English language skills, he learned something. It was great!

Joseph, Bob and Benson were reading a children's story. A little background: Benson moved from the streets to Fountain of Hope 5 months ago. He speaks 3 Zambian languages and very good English. He ALSO reads sign language and knows some signs. He picked it up because Bob, who is about my age and arrived from Kenya, is hearing impaired. Benson translates between Bob and me. Joseph, in his early to mid teens like Benson, is Zambian.

They were huddled around a book about The Great Depression called Potato. They hadn't heard of the Depression before, so I explained it to them. Laughing, Benson said, "So America then was like it is here now!"

I had the July issue of National Geographic with me and showed it to them.

We went through the cover article about the Congolese rebel forces who have targeted gorillas in Virungu National Park. Joseph knew a great deal about the situation there, as did Bob and Benson. The article addresses a particular rebel leader who claims to be protecting Tutsis from Hutu forces in the area. He's been accused of using child soldiers and committing other war crimes. I asked them if they knew about child soldiers, and they did. They knew everything. When they heard me mention Hutus, Joseph went into detail about the Rwandan genocide and described it to us. He told Benson and Bob about "the year 1994". I was amazed.

After the article, they requested more information on gorillas, so we went through a book called The Great Apes.

By the time their recess ended, we had covered The Great Depression, the political turmoil in the DRC, the Rwandan genocide, Ugandan schools, Dian Fossey's life, and Jane Goodall's research.

In the early afternoon, there was a power outage and the lights went out. Rather than leaving, everyone opened the windows and continued looking at books in the patches of sunlight on the library benches. Lubuto is definitely the place to be.

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Lubuto Library Visit for SCECSAL Conference Attendees

The organized visit to Lubuto from the conference went well. Conference attendees had the choice of several local library/archives tours in the same time slot, but many people registered for Lubuto. Vasco, Eleni and I presented the information on Lubuto to the group, and it began as a more formal presentation structure quickly evolved into a question and answer session and then to an informal discussion. I liked the suggestion to document stories told by the children who use Lubuto in addition to documentation of Zambian stories for the purpose of cultural preservation. We introduced the student/library employees, and the visitors were delighted to meet young Zambians learning library operations and services.

The attendees themselves were an impressive and diverse group. There was an American librarian who did library development in Rwanda and is building a public library in Namibia as part of her doctoral studies. A librarian from the Africa and Middle East division of the Library of Congress. A British professor in information literacy. A man from the Ministry of Education in Zambia. Another American from UNC-Chapel Hill's collection development. I had the opportunity to discuss their careers and my plans for Lubuto and my career, and I will make an effort remain in contact with them. The tour made a positive impression on them, and I hope they shared their experience with their colleagues. If Lubuto had not inspired a colleague of mine to share her experience, I would never have been involved myself.

The attendees themselves were an impressive and diverse group. There was an American librarian who did library development in Rwanda and is building a public library in Namibia as part of her doctoral studies. A librarian from the Africa and Middle East division of the Library of Congress. A British professor in information literacy. A man from the Ministry of Education in Zambia. Another American from UNC-Chapel Hill's collection development. I had the opportunity to discuss their careers and my plans for Lubuto and my career, and I will make an effort remain in contact with them. The tour made a positive impression on them, and I hope they shared their experience with their colleagues. If Lubuto had not inspired a colleague of mine to share her experience, I would never have been involved myself.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Vasco's Story

Vasco leads classes when they visit the library, manages all the kids, leads programs, recruits kids from the street...generally does everything and keeps the library running smoothly. He introduced me to everyone and everything here, and he also seems to know almost everyone in Lusaka somehow. He's 28-years-old and spent years living on the streets himself. I asked him a few questions to find out how he wound up working here at Lubuto:

Where were you born and where did you grow up?

I was born in Choma [in Zambia] in a village. There are thatched homes with no electricity, so you have to cook with firewood. There's no running water, so you have to fetch water from the stream and carry it back to your village by hand or on top of your head. There are a lot of snakes you have to watch out for. I lived with my father and stepmother there. They were farmers, and they farmed maize, pumpkin leaves, rape, pineapples, mangoes, guavas, sugarcane, bananas, green peppers, carrots, and so on, and I helped. The chief [of the village] who was there then is still there. He wears animal skins and uses a zebra tale to swat flies. People in the village practice witchcraft. Lots of people have a negative attitude towards witchcraft, so I don't want to say too much about it. I don't practice it. I'm a Christian...but I'm a Buddhist inside! [laughs]

How did you end up on the street?

My father died when I was about 12 or 14 or so, and things became very hard. We had a lot of things [before he died]: three tractors and animals, and people took them, so we were left with nothing. I started staying with some people who abused me, so I hopped on a train. I didn't pay. You do it by hiding in the toilet and keeping the door closed with your feet, so people try to use it and think it's out of order. I went to Livingstone [in Zambia at Victoria Falls] and then Kitwe in the copperbelt [the biggest mining industry in Zambia] then Ndola [Zambia] and then Lusaka. Seven years all together. Life on the street was really hard, and I ended up doing things I wasn't supposed to do.

How did you get off the street?

I almost committed suicide and was taken to the hospital. From the hospital they brought me here to the shelter. I lost hope in life and thought nobody cared for me or loved me. But I started going to school here and became the very first street kid to complete school in Lusaka. Life was really interesting at the shelter because I learned how to trust people again, respect people and their things and how to love again. I had lost all of that. I decided to dedicate my whole life to helping the street children because I've been there, and I believe that if I can change, other kids can change, too. The management asked me what I wanted to when I finished school, and that's what I told them. That was in 2004, but I was supposed to complete school in 1999. It was hard because my friends were completing their grade 12 exam while I was completing grade 7.

How about the Lubuto Library?

I liked reading a lot, so I decided to get really involved in the library.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

SCECSAL Conference

I had been looking forward to SCECSAL (Standing Conference of Eastern, Central & Southern Africa Library and Information Association) for quite some time. I attended the ALA Conference (American Library Association) last summer in Washington, D.C., and I was curious about its African counterpart. It happened to be in Lusaka, which was very lucky for me because I wouldn't have been able to travel to another country had it been held elsewhere in Africa. The conference center is in the city, but there are groups of wild impala running through the parking lot and eating grass in front of the large windows. The opening ceremony was also distinctly African, highlighted by the Zambian dance troupe performing Zambian dances in sync with traditional drumming. A comparable opening ceremony at ALA would include what that might be typically American? Cheerleading? It was an interesting conference commencement that wouldn't translate in many other places.

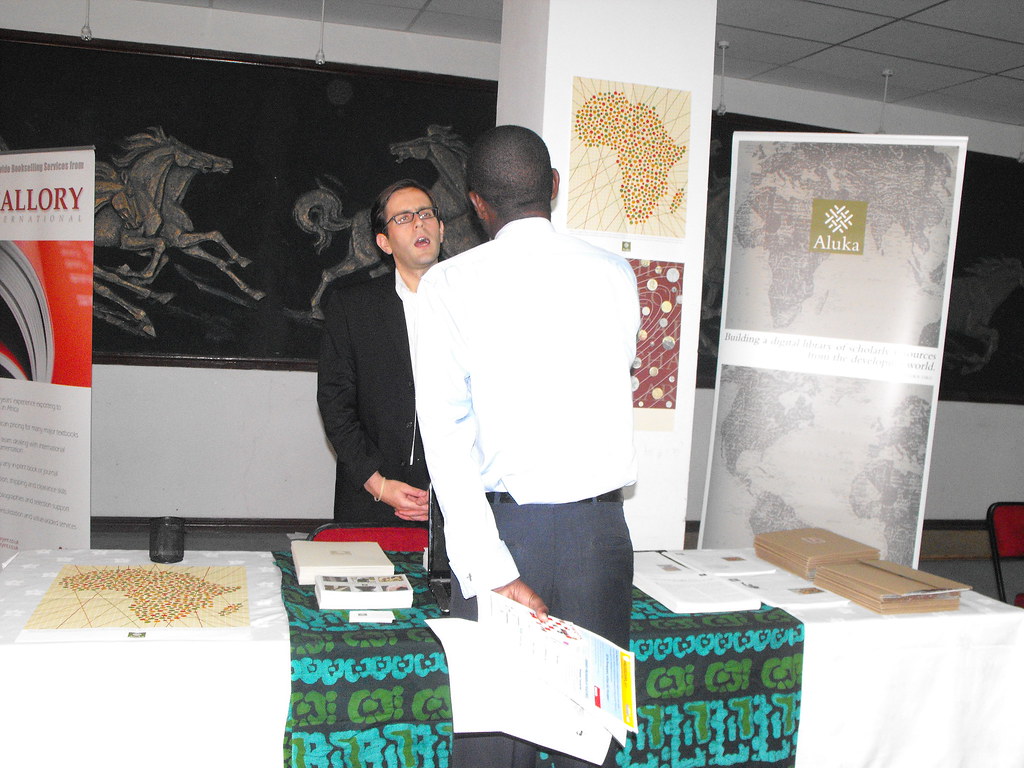

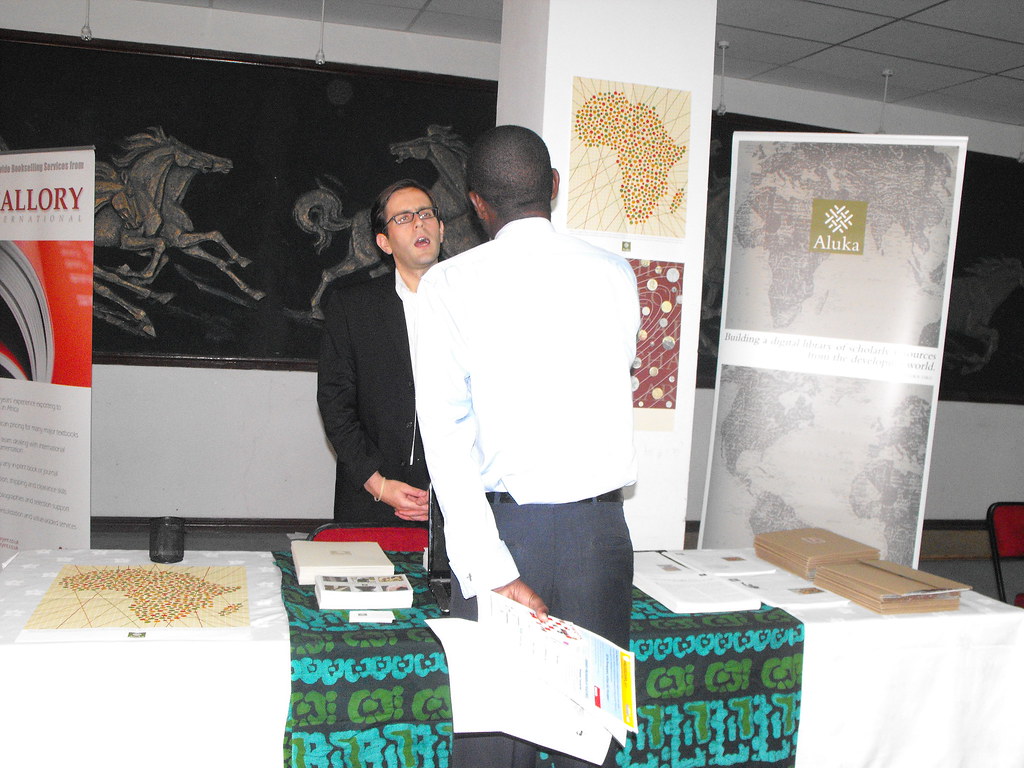

Near the lobby of the conference center was a room with various booths: publishers, non-profit library organizations, etc. I talked to the EBSCO representative from their South Africa division and browsed the materials at the IFLA table next to Aluka. Aluka is a non-profit that digitizes academic materials including cultural objects for and about Africa. Now affiliated with JSTOR, it should be gaining momentum and covering more ground. Aluka provides free access for many African universities and institutions and makes these resources available to African scholars, anthropologists, historians among others. I have a background and interest in African art and culture, so it was serendipitous and potentially very useful.

During the tea break, I met a law librarian about my age from Zimbabwe who assured me that I could return to Harare. He was very nice, and I refrained from jokes about laws and Zimbabwe. He offered to arrange my trip (yes, hotels are still operating.) He told me it was completely safe as long as I didn't ask questions about politics in public and risk being labeled a journalist. I believe I'd be relatively safe as a white person in a city since the violence was mostly targeted at MDC supporters in rural areas, but there wouldn't be much to see there. I'm sure most people I knew are in South Africa, and I'm sure most places are empty. I just appreciated his optimism. Cool librarians are everywhere.

I had the opportunity to attend presentations and lectures, as well. I chose ICT in Information Science and Service because I did a great deal of research on ICTs and Zambian e-government resources for a class last spring. The presentations generally addressed strategies and initiatives to connect rural communities with technology. Similar topics appear again and again in library science, but the Gender and Marginalized Groups session's lectures were new to me and I learned a lot. Prof. J.R. Ikoja-Odongo from Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda discussed the relevance of women farmers' information networks as viable contributions to Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Unique to developing countries, I probably wouldn't have had exposure to this issue unless I was researching an adjoining topic. I wasn't expecting such a focus on rural communities although they comprise such a large percentage of the population in Africa. I guess I'm accustomed to a focus on urban areas, but it's hard to say whether it's a result of living in New York and working for an urban public library or Americans tend to leave rural areas out of the equation when it comes to addressing marginalized groups. The final presentation in the Gender and Marginalized Groups session was given by Naomy Mtanga, Prof. of Library Science at the University of Zambia, about Lubuto Library Project's contribution to MDGs for vulnerable children. There were tons of questions following her presentation, which I hope reflects the interest of professionals in sub-Saharan Africa. Most librarians at the conference are living and working in places where they've undoubtedly been exposed to vulnerable children. Their consideration for this topic comes with an understanding not shared by Westerners who have vague ideas about "poor African children", so the resulting discussion was informative and sharp.

I wish IFLA wasn't next month. I'll be here in Zambia, and the conference is in Montreal this year. It would be nice to see a few of these African librarians again. Last year, it was in Durban, South Africa, so I'm a year late in Africa and was a year early in North America. I'm about 8 or 9 hours from Durban in Lusaka and about the same from Montreal in New York. I should stop obsessing. I guess one convenient library conference locale per year is enough for me.

Aluka booth with Aluka's User Services Specialist Michael Gallagher:

IFLA booth (me):

Near the lobby of the conference center was a room with various booths: publishers, non-profit library organizations, etc. I talked to the EBSCO representative from their South Africa division and browsed the materials at the IFLA table next to Aluka. Aluka is a non-profit that digitizes academic materials including cultural objects for and about Africa. Now affiliated with JSTOR, it should be gaining momentum and covering more ground. Aluka provides free access for many African universities and institutions and makes these resources available to African scholars, anthropologists, historians among others. I have a background and interest in African art and culture, so it was serendipitous and potentially very useful.

During the tea break, I met a law librarian about my age from Zimbabwe who assured me that I could return to Harare. He was very nice, and I refrained from jokes about laws and Zimbabwe. He offered to arrange my trip (yes, hotels are still operating.) He told me it was completely safe as long as I didn't ask questions about politics in public and risk being labeled a journalist. I believe I'd be relatively safe as a white person in a city since the violence was mostly targeted at MDC supporters in rural areas, but there wouldn't be much to see there. I'm sure most people I knew are in South Africa, and I'm sure most places are empty. I just appreciated his optimism. Cool librarians are everywhere.

I had the opportunity to attend presentations and lectures, as well. I chose ICT in Information Science and Service because I did a great deal of research on ICTs and Zambian e-government resources for a class last spring. The presentations generally addressed strategies and initiatives to connect rural communities with technology. Similar topics appear again and again in library science, but the Gender and Marginalized Groups session's lectures were new to me and I learned a lot. Prof. J.R. Ikoja-Odongo from Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda discussed the relevance of women farmers' information networks as viable contributions to Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Unique to developing countries, I probably wouldn't have had exposure to this issue unless I was researching an adjoining topic. I wasn't expecting such a focus on rural communities although they comprise such a large percentage of the population in Africa. I guess I'm accustomed to a focus on urban areas, but it's hard to say whether it's a result of living in New York and working for an urban public library or Americans tend to leave rural areas out of the equation when it comes to addressing marginalized groups. The final presentation in the Gender and Marginalized Groups session was given by Naomy Mtanga, Prof. of Library Science at the University of Zambia, about Lubuto Library Project's contribution to MDGs for vulnerable children. There were tons of questions following her presentation, which I hope reflects the interest of professionals in sub-Saharan Africa. Most librarians at the conference are living and working in places where they've undoubtedly been exposed to vulnerable children. Their consideration for this topic comes with an understanding not shared by Westerners who have vague ideas about "poor African children", so the resulting discussion was informative and sharp.

I wish IFLA wasn't next month. I'll be here in Zambia, and the conference is in Montreal this year. It would be nice to see a few of these African librarians again. Last year, it was in Durban, South Africa, so I'm a year late in Africa and was a year early in North America. I'm about 8 or 9 hours from Durban in Lusaka and about the same from Montreal in New York. I should stop obsessing. I guess one convenient library conference locale per year is enough for me.

Aluka booth with Aluka's User Services Specialist Michael Gallagher:

IFLA booth (me):

Sheadrick: Lubuto Library Patron

Age: 12

Grade: 5

Hometown: Ndola, Zambia

Language: Bemba

Books: Creepy Crawlies by Hans Post and Irene Goede

Do Animals Go to School? by Steve Parker and Graham Rosewame

Lubuto Classification: Stories, Level 2

Short Interview:

Sheadrick: This is a grasshopper.

me: Yes, it is. Why do you want to read Creepy Crawlies?

Sheadrick: Because I can learn something in here. I'm learning to read, and these words are good for me.

me: Do you like bugs, too?

Sheadrick: Yes!!

me: Why do you want to learn to read?

Sheadrick: It is nice. All my friends outside know how to read. Some of them are 14, some of them 9 years. My friend is very good. She'll come here, and you'll meet her.

me: Good, I'd like to meet her. Which book is better, Creepy Crawlies or Do Animals Go to School?

Sheadrick: Creepy Crawlies.

me: Why is it better?

Sheadrick: Because I know more of the words.

me: Last question: who do you think would win in a fight, a grasshopper or a spider?...Stop laughing, I really want to know!

Sheadrick: A spider!

me: I knew it. But grasshoppers are cool, right?

Sheadrick: yes.

me: Can I take your picture? I'm going to put this on the internet. I'll show it to you when it's done.

Sheadrick: Yeah, sure.

Monday, July 14, 2008

Getting to Know Lubuto

My footsteps create little clouds of dust on the dirt roads in Kamwala, an area in Lusaka. It's the dry season, and each afternoon light winds bring giant clouds across the African sky. Even over the drab cityscape of Lusaka, the sky's size is commanding and dwarfs the skies of the American West, from what I can recall. Competing with the sky is the colorful stone wall of murals encompassing the Lubuto Library Project and adjacent Fountain of Hope school and shelter for vulnerable youth. The surrounding neighborhood is calm although steps away from the busy Kamwala market and shops. Above the occasional passing cars, the sound of children playing can be heard outside the stone wall.

The view from the road:

On my first day, I learned where the hundred or so children come from and why they're here. Many of them live in the Misisi compound which lies across a rocky, grassy field nearby. It's an impoverished area, plagued with cholera and other waterborne diseases in the rainy season when it floods. These kids attend school at the Fountain of Hope along with the kids at the shelter and some from Kamwala, too. Some of them reside in Kamwala but can afford to attend schools with better resources, so they stop in after school to play basketball and run around and read in the library. The children who stay at the shelter are mostly "street children" who have been successfully recruited from their rough lifestyles. Several kids, I'm told there are about 7 right now, who can often be found browsing the library, still live on the street and aren't ready to leave for various reasons: their group of friends become their family units, they are afraid to be drafted into the military if they're out in the open at a shelter, they want to continue selling and stealing, etc.

Playing outside:

For nearly everyone here, English is a second language and a general goal for them is becoming better at speaking and reading it. Nyanga, a Zambian language, is most widely spoken. Zambian languages Bemba and Tonga are also common here, and a few speak Lenje, too. Some speak Swahili because they've arrived from Tanzania or Kenya. A Tonga speaker, Emmanuel, gave me a Tonga name, Chipego, meaning "gift", but everyone calls me Holly.

The view from the road:

On my first day, I learned where the hundred or so children come from and why they're here. Many of them live in the Misisi compound which lies across a rocky, grassy field nearby. It's an impoverished area, plagued with cholera and other waterborne diseases in the rainy season when it floods. These kids attend school at the Fountain of Hope along with the kids at the shelter and some from Kamwala, too. Some of them reside in Kamwala but can afford to attend schools with better resources, so they stop in after school to play basketball and run around and read in the library. The children who stay at the shelter are mostly "street children" who have been successfully recruited from their rough lifestyles. Several kids, I'm told there are about 7 right now, who can often be found browsing the library, still live on the street and aren't ready to leave for various reasons: their group of friends become their family units, they are afraid to be drafted into the military if they're out in the open at a shelter, they want to continue selling and stealing, etc.

Playing outside:

For nearly everyone here, English is a second language and a general goal for them is becoming better at speaking and reading it. Nyanga, a Zambian language, is most widely spoken. Zambian languages Bemba and Tonga are also common here, and a few speak Lenje, too. Some speak Swahili because they've arrived from Tanzania or Kenya. A Tonga speaker, Emmanuel, gave me a Tonga name, Chipego, meaning "gift", but everyone calls me Holly.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Lubuto and Me: An Introduction.

I'm a student at Pratt Institute's School of Information and Library Science, and I have been working as a librarian trainee at Brooklyn Public Library since I began my studies in August 2006. l hope to finish in December 2008 upon completion of an independent study and a practicum addressing the Lubuto Library Project.

Last August, the Head of Collection Development at Brooklyn Public Library, Barbara Genco, attended the IFLA (The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions) conference in Durban, South Africa where she met Jane Kinney Meyers, Lubuto Library Project's founder. Barbara returned from the conference and gave me information on Lubuto and put me in touch with Jane because she knew I had lived in Harare, Zimbabwe and had an interest in Africa. Jane Kinney Meyers and I began exchanging emails and having phone meetings on Lubuto's progress and future as a non-governmental organization. After discussion on my site visit and work at Lubuto, I applied for and received the Nasser Sharify Fellowship for International Librarianship and prepared for my stay in Lusaka, Zambia.

I met with Jane at Lubuto's headquarters in Washington, D.C. and visited the site where donated books are stored and processed according to Lubuto's classification system before they're shipped to Zambia. I selected a few books to pack in my suitcase and share with the children at Lubuto myself: Mufaro's Beautiful Daughters by John Steptoe, Nelson Mandela's Favorite African Folktales, and I Live in Brooklyn by Mari Takabayashi. During my three months as a children's librarian, I read Mufaro's Beautiful Daughters to children at the Brownsville branch library in Brooklyn and everyone really enjoyed it. I chose I Live in Brooklyn for an obvious reason, however trite it may seem. Nelson Mandela's selected stories happened to coincide with his 90th birthday, too (I had no idea.) The last detail before my visit was, of course, to ship myself to Zambia, and here I am.

Doris Lessing, recipient of the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature, penned African Laughter: Four Visits to Zimbabwe, which was first published in 1992, an insightful non-fiction account of her experiences in Zimbabwe. It chronicles a country born with incredible obstacles struggling to find its balance. I decided to read it in light of the recent political turmoil and my own reflections on the country in 2003. I had the serendipitous fortune of discovering passages addressing books and libraries and children in Africa reflecting Lubuto's purpose and my personal goals, as well as providing a bit of inspiration:

'I have spoken to many different kinds of audiences in many countries, some of them, as we put it, disadvantaged. This is not the first time I say to young people who will never reach university that there are ways of learning open to them, and no one can stop them learning if they want to learn. With a library and perhaps some sympathetic adult to advise them, there is nothing in the world they cannot study. A good library...is a treasure house, and we take it for granted. It is possible to pick up a book, perhaps by chance, when you are a child, and find in it a world existing parallel to the one you live in, full of amazements and surprises and delights; you can pursue any interest through different countries and cultures, diving back into history and forward into the future; you can exhaust one interest and then find another, or, turning over books, chance on a subject you had never suspected existed-and follow that, with no idea when you begin where it will lead. With a library you are free, not confined by certainly temporary political climates. It is the most democratic of institutions because no one-but no one at all-can tell you what to read and when and how. '

Later in the book, she describes a library in need:

'There are rejects from better libraries, and among them might be books the children would enjoy, but no attempt is made to differentiate between them. Perhaps the idea is, better any books than none at all. But there is such a hunger for books, for advice about books, in this country...Books remain as influential as they ever were, in countries like Zimbabwe. It is not possible to exaggerate the influence of books, even one book. Dambudzo Marechera, author of House of Hunger, described how...he found a thrown-out Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopedia. It changed his life.'

I identified these passages with what solutions to these problems I already knew Lubuto had addressed:

1. Lubuto provides an organized collection of books filtered through a collection development plan rather than the disorganized piles of discards from the Western world that Africa often receives.

2. Lubuto provides access to books and information for vulnerable children, some of whom live on the streets and without the luxury of school.

3. Lubuto provides guidance by volunteers and staff, on-hand to assist with book selection and read-alouds, in addition helping liaise content to children with insufficient literacy skills.

Now I can identify them with my own personal interaction with the Lubuto Library patrons, rendering the passages all too true.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)